Skyward Sword: Time Travel, Verticality, and Pirates

Into Another Zelda Dimension

In the last few years I’ve been playing more 3D Zelda titles. Last year I played through Twilight Princess in full, year before that through Ocarina of Time 3D and I’ve been working on Skyward Sword HD more recently. It’s been interesting to follow the path this series has taken, and I’ve dabbled a bit with Wind Waker and Majora’s Mask as well, so while I haven’t finished every title, I’d say I have a pretty good sense of the 3D Zelda series’ trajectory now.

Being primarily a 2D Zelda enthusiast (Link to the Past was my first love), witnessing Nintendo learning how to translate their puzzle-dungeon level design and grab bag of gadgets has been a great experience. Ocarina of Time was something of a mixed bag, with some dungeons relying upon untelegraphed assumptions about what players would naturally do in a 3D space, such as Jabu Jabu’s Belly requiring you to just happen step on to one part of the terrain and cause a platform to separate from the path, while Forest Temple demonstrated that the new dimension could offer new compelling experiences, while maintaining the same level of care in level design offered by Link to the Past or Link’s Awakening. Twilight Princess and Wind Waker had a better sense of what they were doing, but many dungeons in these games moved away from the metroidvania-esque web of unlockable doors towards a more linear and cinematic approach. Any one dungeons might be a combat-focused or environmental puzzle experience like Twilight Princess’s Forest Temple and City in the Sky, respectively, and each room may have its own unique challenge, but in totality they were simple linear adventures. Where they lacked in complexity of design, the Gamecube titles excelled in their visual and sound design, with strong environmental storytelling to help players forget that they were being lead so heavily. The change towards more linearity was hidden quite well and the trade off is arguably worth it, but come Skyward Sword, Nintendo would demonstrate that there are things that 3D can do that 2D can only dream of. Not only in terms of immersion in the environments, but in terms of puzzle and combat design.

Skyward Sword’s Wii release, however, proved troubled. While it looked gorgeous on a CRT, the Wii’s inability to display HD content and its legacy hardware’s limited capabilities meant that Skyward Sword was a subnative blur on modern displays, with horizontal artifacting distracting from its painterly aesthetic. Concerns over the novel motion control scheme was enough for Nintendo to plaster reminder graphics across the bottom left and right hand sides of the screen by default, further masking the game’s art direction. Combine this with a handful of annoyances such as regular unskippable cutscenes announcing you’d picked up a crafting item or rupee, lack of proper telegraphing of NPC sidequests and key dialogue, as well as needing a new wiimote or dongle to play the game properly and one can understand why Skyward Sword’s first outing was met with some grumbles. At the time I was finishing high school and beginning to move away from consoles entirely in favor of PC, and these issues were hard to ignore. I also found replacing the seamless interconnected world I expected of Zelda with the hub world of Skyloft offensive to my 2D Zelda sensibilities. I played through the first few dungeons and put it down in favour of other titles.

That was until last year when I finally bit the bullet and purchased a Switch Lite. The hardware wasn’t–and isn’t–my favourite, but Link’s Awakening and Skyward Sword getting rereleases and New Pokemon Snap calling me finally convinced me to buy in. At this point–a year after first starting it–I’ve finished Skyward Sword HD and am ready to admit: I should’ve powered through my frustrations and played more back in 2011.

A Synthesis of Lessons Learned

Skyward Sword takes the dungeon design of Ocarina of Time, Twilight Princess, and Wind Waker and elevates its predecessors in a way no Zelda title has since Link to the Past. Not only that, it does so with such deliberate elegance that I can’t quite believe how long ago Skyward Sword first released. In a time when the Zelda series is rediscovering open world design fifteen years behind the rest of the world, playing Skyward Sword offers such a ruthlessly focused experience with such tight design that it’s hard to reckon with this being the final Zelda title before Breath of the Wild radically shifted the series’ principals to something altogether unfocused.

Image via Zelda Wiki

The HD rerelease does a fair bit to alleviate the aforementioned bits of UX friction. Cutscenes and dialogue are less frequent (and skippable!) and faster respectively, sidequests and key story dialogue are telegraphed with a thought bubble above NPCs heads, and HD implements the option of playing the game with a whole new control scheme that offers an analog stick replacement for the wiimote motion controls. Image quality is stellar, even in handheld mode, and while some of the game’s original painterly aesthetic is lost in the transition to a higher resolution, the trade off is more than worth it and the aesthetic is largely maintained and certainly gorgeous. In sum, it’s a strict improvement over the original in almost every respect, and where I’m typically the first to pick up the original release of a game over rereleases, the handheld nature of HD and its comprehensive improvements make this an exception.

Preamble and release-specifics aside, what about Skyward Sword sets it apart? There are two main points here: first, Skyward Sword’s dungeon design is the best the 3D Zelda series has to offer; And second, its character writing and narrative elevate what is already a fantastic game to an exceptional experience. There are other things worth ink–the gorgeous art and music, the combat (even with a wiimote!) being more precise and skillful than first impressions would indicate–but this duet of level design and character writing are the places in which Skyward Sword sets itself apart from other titles in the franchise and indeed justifies the move from 2D to 3D more than 10 years after it happened. Its use of physicality and vertical space would be impossible to replicate in a 2D game, and its characters are elevated massively by their animation and dialogue. Truly, Skyward Sword is a distillation of what makes Zelda games so enthralling.

I’ll cover the narrative aspects of the game and how Skyward Sword uses trope and abstraction to tell a highly affectual story in an eventual follow up, but for now the focus is level design. All of Skyward Sword’s dungeons are worth going over, but in the interest of brevity, I’ll focus on the two Lanayru dungeons: Lanayru Mining Facility and the Sand Ship. These dungeons each have extremely strong concepts, engaging core gameplay conceits, and make brilliant use of the 3D environments of the game. There are no duds–honorable mention to the Ancient Cistern in particular–but these are the cream of the crop.

Lanayru Mining Facility

Lanayru Mining Facility is the third dungeon of the game, located in the arid wasteland of Lanayru. Upon arriving, Link is introduced to a few key concepts right out of the gate. Quicksand demands Link run across gaps using Skyward Sword’s new stamina bar or else sink and perish. The previous dungeon, the Earth Temple, had introduced bombs and Lanayru introduces special doors with basketball hoop-esque goals to throw bombs into, causing the doors to fall, giving Link the opportunity to use their fallen backsides as respite from the quicksand or to uncover hidden areas. Later on, Link gains the ability to pick up bombs with a remote control flying beetle–one of the most shockingly effect new items–which he can then drop from above into these doors to open them without being in throwing range. Some of the local wildlife, the hermitcrab-esque Ampilus, interact with both the quicksand and these doors as their hard shells are left behind as a platform when they're killed. These Ampilus shells can be then used to create a platform to throw bombs into doors, or to traverse the quicksand itself. Other Lanayru mechanics include hidden traversable platforms beneath the sand, Ampilus eggs which serve as electrified ‘keys’ to turn on machinery, as well as a bevy of bombable objects. All introduced in the lead up (as in, before the dungeon even begins properly!) to the Mining Facility. It’s dense, to say the least.

Image via Zelda Wiki

Among all these mechanics is one that stands out as the defining characteristic of the region, are the timeshift stones. Timeshift stones are crystals that, when hit, create a spherical space around the stone that is transported back in time to when Lanayru was a lush lake rather than a desert. Not only does this change the terrain (making quicksand into solid soil, for instance) but also brings the long-rusted and dysfunctional mining equipment back to operating order. Hovering minecarts, chatty mining robots, conveyer belts, automated doors, among other things all come to life when in the radius of an active timeshift stone. Barbed wire barriers vanish or are replaced by electronic laser gates, bridges that had collapsed return to their original glory, and dirt and grime that had collected around the area–including piles of dust, sand, or quicksand–often disappear. The transformation is one that is mechanical and yet wholly environmental.

As a gameplay device, timeshift stones are one of my favourites in the series, and as a storytelling device it is perhaps even more impressive. Zelda has often taken on time travel mechanics, but it usually takes the form of a parallel world that is wholly separate such as adult versus child Link in Ocarina of Time. Localized time travel creates intuitive but interesting puzzles in a seamless contained space, and hinting towards the history and knowledge of a civilization that the denizens of Skyloft had forgotten. The choice to make timeshift stones effect a sphere of influence, rather than only the ground surrounding them, allows for verticality to be introduced by, for instance, having a timeshift stone move overhead while Link stays in its radius below, or for a conveyer belt to escort a timeshift stone to high ground while Link traverses the area. The options are limitless and the joy of seeing the area go from rust, dust, and grey to vibrant reds with glowing cyan electronics or green grass is a visual treat that accentuates the puzzles, teaching the player to associate the bloom of color with fun and an explosion of dynamism.

As Link traverses the ruins of Lanayru looking for an entrance to the Temple of Time, a question that would lead him to the Mining Facility proper, obstacles blend the different Lanayru puzzle mechanics in increasingly novel and interconnected ways. Throwing bombs into cages to destroy the rubble within and uncovering a timeshift stone and the ability to chat with a robot who knows the area, or dropping bombs into hoops to create platforms to run across quicksand, giving access to a platform above where you can drop a minecart onto a track before hitting a timeshift stone to activate it. These introductory puzzles really emphasize the benefits of Skyward Sword’s hub-world design. Link encounters all of these mechanisms and puzzles before even entering the dungeon proper, and is given a more open environment to experiment with how they intersect prior to getting into the thick of it. This is something that simply wouldn’t work with Zelda’s traditional proto-open world design. By walling the environments into the silos of Faron, Eldin and Lanayru, each area becomes a highly tuned mega-dungeon where the introductory areas are open sandboxes that introduce core mechanics for the area, giving space for the player to explore and play with them, and the dungeon are elevated experiences that assume foundational knowledge is already present and offers denser, more complicated level design. By replacing a seamless world with these large but independent levels, Nintendo is able to offer the exploration one would expect from Zelda–complete with sidequests and locked off areas that players can return to when they find new items–while also offering dungeons that are more substantive than the faire offered in the Gamecube titles, and without the esoterica of the Nintendo 64 titles.

These pre-dungeon areas also play with scale to offer a variety of puzzle experiences. For example, the area wherein Link uncovers the hidden entrance to the Mining Facility is an enormous spiderweb-shaped ruin, bordered by cliffs and crumbling into the quicksand. Within this area, Link can only see the limits of the space between the spiderweb’s strands while on the lowground, but upon crawling up the walls, can see the shape of the area much easier. By using the map, Link can see the exact shape of the area–including places where the ruins had crumbled so completely so as to leave only a wall beneath the sand where he can run on ‘invisible’ platforms unaffected by the quicksand. Finding ways to climb the walls, navigate the quicksand, or move bombs around to create platforms is the primary puzzle of this area, but when Link is told he must find a series of locks to turn on the generator that powers the Mining Facility and access it, he finds one room mini-dungeons similar to the shrines in Breath of the Wild or the stray mini-dungeons hidden throughout the world of Link to the Past, et al., hiding them. The open areas give players room to experiment with the mechanics of Lanayru, and the mini dungeons introduce new paradigms for how to utilize those mechanics in ways that may be more applicable within the dungeon itself or (I suspect) find space for mechanics that are fun but didn’t quite fit within the dungeon. The use of both expansiveness and closedness gives a lot of room for players to get comfortable and are highly effective tutorials that are evocative and, crucially, fun!

Once inside the facility proper, we see room-wide timeshift stones, as well as some new enemies such as Beamos–which require horizontal slashes and a stab to defeat–that animate only when a timeshift stone is active over their rusty husk. Levers are situated on the walls that Link can run up to in order to reach and toggle some of the electrified fences on or off and the conveyer belts’ directions. Minecarts containing timeshift stones allow for autoscroller-esque sequences where Link has to maneuver through hazards while keeping up with the minecart. Each component builds on the last.

Once inside the facility proper, we see room-wide timeshift stones, as well as some new enemies such as Beamos–which require horizontal slashes and a stab to defeat–that animate only when a timeshift stone is active over their rusty husk. Levers are situated on the walls that Link can run up to in order to reach and toggle some of the electrified fences on or off and the conveyer belts’ directions. Minecarts containing timeshift stones allow for autoscroller-esque sequences where Link has to maneuver through hazards while keeping up with the minecart. Each component builds on the last.

Not far in, Link is given the dungeon item, one returning from the Capcom-developed Minish Cap: the Gust Bellows. The bellows’ core concept of an infinite jar of air you can direct towards piles of sediment to uncover what’s beneath, blow around enemies, or spin a fan with invites a host of puzzle concepts and Skyward Sword offers the player all of them. Lanayru employs many of these aforementioned uses liberally and it does so in a way that feels natural. Elsewhere in the game, Link can use the bellows to manipulate the direction rickety platforms swing, or help side characters clean their homes. It’s not an item that has broad usage the way the bow or bombs do, but for an item that requires the developers to actively place ‘locks’ for the bellows to open, it’s one of those with the most fun locks.

The bellows figures into the facility in a number of ways. Its most basic and immediate use is to blow away piles of sand to uncover switches and timeshift stones, or to move sand out of the path of crates that can be pushed to create platforms or depress pressure pads permanently. As Link explores further into the facility however, the uses are more often about manipulating platforms with fan-shaped screws that propel them along coiled wires. While the platforms look like rusted spikes in the present, activating a timeshift stone will regenerate the fans and allow Link to move the platforms around, creating a player-propelled moving platform. Minish Cap had done something similar with its lily pads–allowing the player to blow air to serve as a propulsion mechanism, something that Skyward Sword mimics elsewhere with platforms suspended by thin ropes–but the change from lily pads on water to these mechanisms feels different and novel. The puzzles vary as well. You may be trying to blow your platform along a wire to keep up with a timeshift stone moving autonomously in a minecart parallel. Or, you may be simply repositioning a platform to be jumpable from another vantage. The mechanic relies heavy on multiple parallel paths, either for Link or some other object, running in parallel with obstacles that force the player to consider where they may be able to access from another perspective, or demands a bit of multitasking as pushing a platform along demands being within a certain range.

The minecarts with timeshift stones within them work on a similar gameplay axis. Since the electrified minecarts move autonomously, they create auto-scroller-esque segments that demand Link keep up with them, as new platforms or obstacles materialize in front of him as the timeshift stone hits them and then fading behind him. Just as the blowable platforms often demand Link find a way to run alongside the platform, the minecarts add a timed element to that, remixing the puzzle room to room. The penultimate room of the facility, which is an enormous area that serves as an early teaser for upcoming mechanics, features a segmented minecart track with timeshift stone that the player needs to open doors (using the bellows to spin a pinwheel mechanism), run on platforms the timeshift stone creates, and dodge Beamos attacks on alternating sides, using the minecart itself as a shield. It’s a fantastic final lap and this room also pulls together quicksand mechanics and others as a sort of puzzle ‘boss’-rush.

Lanayru Mining Facility’s final boss is also one of my favourites: Moldarach, an enormous cyclopian scorpion with glowing eyes in the grip of its two pincers. Predictably, the two glowing eyes serve as weak points, and Link has to weave his sword swipes between the jaws of each pincer to strike the glowing eye. Simple, well telegraphed, and fun! Once Link strikes both eyes enough times, the pincers explode and Moldarach burrows into the sand under Link’s feat. Having mastered the bellows throughout the facility’s puzzles, the player will know to whip out the trusty bellows and blow all the sand away to uncover the scorpion's carapace. Moldarach will continuously move to make things difficult, but upon being fully revealed will pop out of the sand and present the eye in the middle of its head as the final weak point. Stab it, blow away some more sand, repeat, and you’ve finished a fantastic dungeon.

Lanayru Mining Facility is great front to back, and is one of the strongest early dungeons in any Zelda dungeon. Its core mechanics are varied, work well in unison, and are each thematic and give space for the player to sit back and think “damn that’s cool”. Each mechanic builds so elegantly on the last, creating either increasingly complex synergistic jenga towers of interconnected ideas or replicating a simple yet engaging gameplay loop in new contexts. The facility shows the ways in which 3D elevates spatial puzzles–as I write, I’m reminded of games like Riven and how their 3D environments and objects created puzzles that its adventure forebears simply could not convincingly pull off–and shows off how those spatial puzzles can work in large open areas and dense enclosed rooms alike. That said, the verticality of this first Lanayru section isn’t really the emphasis. That will come on the second visit.

The Sand Ship

Returning to Lanayru, you enter into a familiar area, but having cleared a couple dungeons since, Link is well equipped to explore areas that were previously inaccessible. Having earned the clawshots, AKA the hookshot, from a timed exploration puzzle–wherein Link collects drops of light without being attacked by large white golems around Lanayru–the player is given the ability to pull himself to targets littered around the area, allowing Link to traverse bottomless caverns. Learning from Twilight Princess, Skyward Sword immediately gives the player the ability to fire a second clawshot while hanging from the other. This mechanic instantly gives Skyward Sword’s clawshots the level of verticality that Twilight Princess really only attains in its City in the Sky. Jumping between pillars, canyon walls, and hoodoos is fun, and teaches the player to look up–not just around. Returning from Twilight Princess as well are floating Peahats that serve as living clawshot targets. A new layer of environmental interaction to the Peahats, Link can now use the Whip–attained from the dungeon prior–to pull growing Peahats from the ground and into the air to use as targets. Overall, the clawshot immediately brings a degree of verticality to a Lanayru that was, on first visit, rather flat.

Traversing a canyon and adjacent cavern, Link is guided to another open area: the Sand Sea. Overseeing the enormous body of quicksand is a pier, where Link finds a quicksand-stuck boat housing a timeshift stone and its captain–a robot who had long rusted. Toggling the timeshift stone will free the boat, reveal the quicksand as the remains of a lush ocean, and prompt the captain to ask Link to seek out his old ship, which had been commandeered by pirates and contains one of the sacred flames he’s looking for. Off you go.

As before, the second Lanayru section has some preamble prior to the dungeon. Unlike before, while there are a handful of new mechanics (such as the clawshot targets and peahats), this segment is much more about thematics and emphasizing the third dimension. You make three stops on your way to find the pirate ship, two of which introduce a key mechanic for the upcoming dungeon, one of which has its own unique gimmick.

The first is a stop at the captain’s cabin–which is situated at the top of an enormous group of hooboos that tower above the sea. This area is mostly about introducing the player to the clawshot, but it also includes a mechanic that will come up again later: a network of ziplines that allow Link to ride up and down between the hooboos. There’s not much else here, but this one of the most starkly vertical areas in the game, and it does a good job of training the player to consider the additional dimension in looking for the path forward. It’s a bit hamfisted–nothing quite like taking the player to a small platform in the middle of the sky and no obvious path forward to teach a player to look up–but it works.

The second stop is a shipyard, which is a mostly self contained gimmick. The main entrance to the shipyard’s bay is closed off and Link is given a network of railways throughout the sky to traverse the area. Unlike the automated timeshifted minecarts found elsewhere, these are traditional wheeled minecarts that Link rides like a roller coaster, leaning left or right to keep the minecart from running off the rails, and selecting the right direction at forks. It’s fun, but doesn’t come up again. The shipyard itself has been occupied by another Moldarach, which is a nice callback to the Mining Facility’s boss.

The final stop, the pirate fortress, introduces a mechanic that will come up repeatedly in Lanayru (and Lanayru-themed) areas in the future: timeshift orbs. These are timeshift stones that can be picked up and moved around the area. The fortress’s interior is a maze of rooms that the player must carry an orb through in order to power the mechanisms that opens the main entrance. Puzzles therein include placing the orb so that it impacts some, but not all, of adjacent rooms (complete with a metal grate at the bottom of the dividing walls to let players see the radius of the orb), or toggling timeshifted blockades between rooms. More than the previous stops–or even the hookshot navigation–this mechanic really trains the player for the upcoming dungeon.

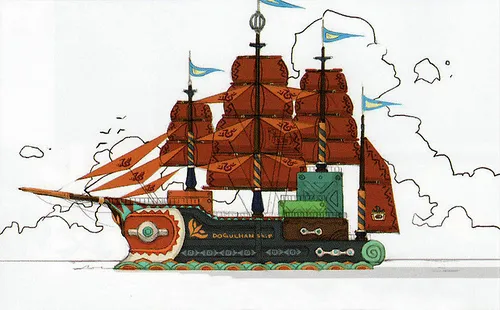

Upon departing the pirate fortress, Link must hunt down the pirate ship. As the pirate ship is invisible, Link uses the dowsing feature (a recurring mechanic used to see the general direction of his current MacGuffin, similar to the scent mechanic in Twilight Princess) to hunt it down, and then blast it with a few bombs to get it to stop. Once aboard, the Ship itself presents a pretty atypical dungeon layout. Zelda isn’t unaccustomed to reinterpreting ‘dungeon’ as a concept, with areas like A Link to the Past’s Thieves’ Town or Twilight Princess’s Snowpeak Ruins creating a dungeon from a more urban environment. The Sand Ship follows this tradition, with the Ship’s top-down design giving the environment a fantastic theme. Carved wooden pillars, floors painted in colorful ocean patterns, brigs and lifeboats, and all manner of ship machinery define the environments of the dungeon.

Where the Mining Facility was a collection of more localized puzzles, the Sand Ship is far more interconnected. Individual rooms may have distinct puzzles–the brig’s door is opened by entering a code hinted at with dials on the floor which Link uncovers by blowing away some settled sand in the room–but the ship itself is defined by a singular timeshift stone hidden at the top of the center mast. From the moment Link arrives on the ship, the game pushes the player to consider the mast’s conspicuous mechanism, and the first half of the dungeon requires navigating through dusty walls–infested by the juvenile Moldarachs–to find a way to activate it. In doing so, Link is confronted with the pirate captain–a mechanical creature that evokes a skeletal impression–who Link defeats, earning the bow. Returning to the main deck of the ship, Link is able to shoot a target to trigger the mechanism hiding the timeshift stone, activate the timeshift stone, clear a group of bokoblin pirates that are scattered around the deck, and then climb up the mast with a series of ladders and ziplines in order to clear the area.

Where the Mining Facility was a collection of more localized puzzles, the Sand Ship is far more interconnected. Individual rooms may have distinct puzzles–the brig’s door is opened by entering a code hinted at with dials on the floor which Link uncovers by blowing away some settled sand in the room–but the ship itself is defined by a singular timeshift stone hidden at the top of the center mast. From the moment Link arrives on the ship, the game pushes the player to consider the mast’s conspicuous mechanism, and the first half of the dungeon requires navigating through dusty walls–infested by the juvenile Moldarachs–to find a way to activate it. In doing so, Link is confronted with the pirate captain–a mechanical creature that evokes a skeletal impression–who Link defeats, earning the bow. Returning to the main deck of the ship, Link is able to shoot a target to trigger the mechanism hiding the timeshift stone, activate the timeshift stone, clear a group of bokoblin pirates that are scattered around the deck, and then climb up the mast with a series of ladders and ziplines in order to clear the area.

The bow, and this central timeshift stone, then become the key mechanic throughout the ship. Unlike previous timeshift stones, which only impacted a radius within the room or a single room at a time, this timeshift stone encompasses the entire ship. Hallways with multiple doors that had been barricaded in the present will now be open, and the mechanisms therein will be available to interact with. With the newfound bow, Link can toggle off the timeshift stone to shoot a target passed a rusted fan into an adjacent room, then toggle the stone back on in order to access it. It works remarkably well, and it emphasizes the interconnectedness of the ship–with many rooms impacting each other, or being mechanically paired with one room being interactable when timeshifted and the other in the present.

It may occur to you, then, that this could get annoying. Needing to leave a room, return to the main deck, shoot the timeshift stone, and then retrace your steps to navigate these paired room puzzles sounds horribly tedious. Thankfully, this is where Nintendo’s hoodoo-based verticality training returns. All over the Ship, light will trickle in to many rooms through vents in the ceiling. By craning his neck and taking out the trusty bow, Link is able to shoot through the grates of the vents to toggle the timeshift stone. This mechanic is utterly brilliant. Where 2D Zelda games have struggled to communicate this type of floor-interconnectedness with a bottom spritelayer indicating where Link could drop into to access otherwise inaccessible areas in Link to the Past and Minish Cap, or levels literally being crushed together in the case of Link’s Awakening’s Eagle’s Tower, Skyward Sword’s 3D environments let Link seamlessly interact with an object two floors above him through a vent in the ceiling.

Not only does this mechanic cut down on the tedium of backtracking, but it also allows for Skyward Sword to create puzzles akin to Ocarina of Time’s infamous Water Temple within a singular room. The Water Temple required Link to access specific areas to raise and lower the water level, and then swim or backtrack to another room entirely to find the related object that’s now interactable. In the Sand Ship, this could happen all within the same room while still impacting the dungeon holistically. For instance, you might have the timeshift stone toggled off to access a room with an electrified gate, then turn it on to get rid of some debris in the room and access a chest. Alternatively, you might turn it off to rust a fan, and then turn it on to toggle on the mechanism you could now access. All natively within the same room or series of rooms, without needing to backtrack, using verticality as a solution.

While this central conceit of the Sand Ship elevates it, the final boss is unfortunately one of Skyward Sword’s few fumbles, requiring the player to use the skyward strike mechanic (done by holding Link’s sword aloft and then slicing once it charges up) to cut some leviathan tentacles that pierce through the Ship. Once the leviathan itself appears, Link shoots it with his bow and swings its sword, and does the whole thing again a few times. It’s fine–pretty standard Zelda faire–but nothing to write home about.

Wrapping Up

All in all, I loved this game. Some fifteen years after its initial release, I’ve made a complete 180 on Skyward Sword with the HD release, and am more than happy to recommend it to any Zelda fan. Unfortunately, I’ve mostly burnt out on the open world design of Ubisoft, Bethesda, and the like, so Breath of the Wild, Tears of the Kingdom, and Echoes of Wisdom have failed to excite me the way Zelda used to. I think I still prefer the game-y-ness of something like Link to the Past, but in a way that I couldn’t have said after playing Ocarina of Time or Twilight Princess, I have a deep appreciation for the level design of the 3D games now.

I do intend to return to Skyward Sword at some point to discuss its writing–I think it does that better than most of its series cohort as well–but I’ll probably do a hero mode (new game+) replay before then. It’ll be a while.